Mossel Bay is located at the eastern edge of a vast triangular region suitable for grazing and crop cultivation, extending 300 kilometers from Bot River in the west to the east. This region is bordered to the north by the Rivier Sonder End, Langeberg, and Outeniqua Mountains, and to the south by the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. At its widest, it measures about 100 kilometers northward from Cape Agulhas to Storms Vlei. Mossel Bay's significance arises from the proximity of the mountains to the coast east of George, causing many rivers to flow directly into the sea and forming deep gorges. Until recently, wheeled traffic could not traverse the coastal belt from George to Humansdorp, forcing travelers to cross the Outeniqua Mountains and continue east through the Langkloof. To the west, there are no practical harbors between False Bay and Mossel Bay, making Mossel Bay the only connection point for land trade from the Little and Central Karoo and the South Cape to maritime trade routes.

This connection started in the late fifteenth century when Portuguese explorers Dias and da Gama obtained sheep and cattle from the Khoi herders in Munro’s Bay. For tens of thousands of years, the ancestors of the Khoisan and the Khoikhoi inhabited this region. Their legacy includes many beautiful place names like Attaqua, Hessequa, Outeniqua, Karoo, Gwaing, and Gourits. The Dutch East India Company’s stock traders, seeking meat for ships, and later the Trekboers, learned to speak Khoi and San languages, resulting in many place names being direct Dutch translations of the original Khoi names. Although the Khoi did not leave buildings, the impressive rock fish-traps from Betty’s Bay to the Gourits River are lasting memorials to the Strandloper people.

To counter French and English threats, the Dutch East India Company established military outposts in Mossel Bay, George, and Plettenberg Bay in 1785, leading to the first permanent buildings in Mossel Bay, now the site of the Maritime Museum. An unlikely event brought the first officer in charge. In 1772, Struensee, the liberal first minister of Denmark, was overthrown and executed in a coup d’état. His private secretary, Hans Abue, fled to Holland and eventually served the Company at the Cape. Abue became the Ensign and Postholder at Mossel Bay for 33 years, dying in 1819 at age 78.

The French and English threats coincided with a wheat shortage, prompting the Company to persuade Southern Cape farmers to plant wheat for Cape Town. Abue’s first task was overseeing the construction of the Granary. In 1807, he supervised the replacement of its unsatisfactory flat roof with a pitched roof. This building, the sole remnant of the Company’s rule in the region, was demolished in 1955 but was rebuilt to the original design in 1988 under Mr. Gawie Fagan’s supervision.

By 1730, a settled farming community existed in the district. The fall of the Company freed economic activity, and Mossel Bay developed as a harbor handling imports and agricultural exports. In 1811, the Cradock Pass above George was opened, providing direct access to the Little Karoo, later replaced by the Montagu Pass in 1848. The first buildings were erected in Church Street in 1820, and English settlers began arriving. The Barrys of Swellendam opened a warehouse in 1827 and built a large warehouse in 1847, now the Protea Hotel by Marriott. Between 1820 and 1902, importing firms built large stone warehouses in Bland Street and Church Street, ten of which still stand.

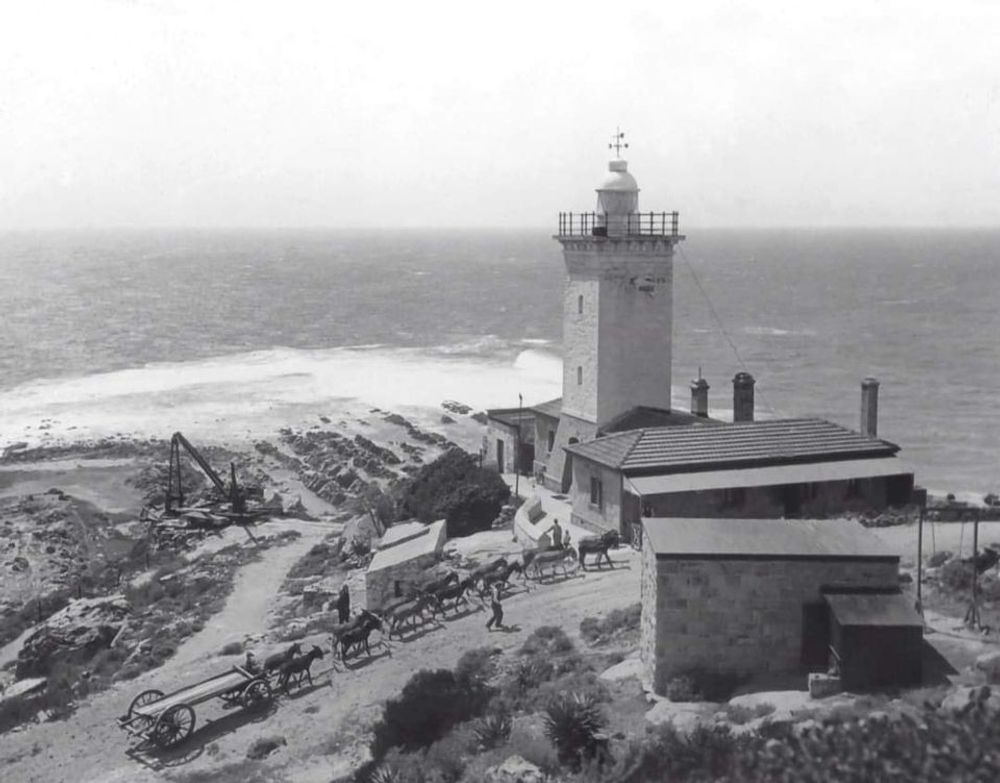

Mossel Bay thus acquired its characteristic appearance as the first predominantly stone-built town in South Africa. Descendants of the Khoi, forming the Coloured community, moved into the town and worked as masons, carpenters, shoemakers, gardeners, stevedores, tailors, bakers, and fishermen, mostly living in the Eastern and Northern parts of the old town. Building in stone continued, with rich merchants’ houses, churches, the town hall, the beach pavilion, schools, quays, the lighthouse, warehouses, and laborers’ cottages all constructed in stone. Initially, creamy-brown stone was used, but after 1900, the beautiful pink stone was used for important buildings. The quality of the masonry improved over time, culminating in the magnificent tower and spire of St. Peter’s Church.

Mossel Bay thrived without rail links. The discovery of diamonds in Kimberley in 1870 made Mossel Bay harbor the nearest sea link. However, by 1885, both Cape Town and Port Elizabeth were connected by rail to the diamond fields, leading to a gradual decline in Mossel Bay’s shipping trade. The arrival of the railway in 1906 and the rail link to Oudtshoorn in 1915 reduced the Little Karoo’s reliance on maritime commerce through Mossel Bay. The late twentieth century brought significant changes, beyond the scope of this paper.

Written by Wesley Gavin

Thank you to Heritage Mossel Bay for supplying all the images and information.

Your dedication to the preservation of Mossel Bay`s history is much appreciated.